Designing for Moments of Crisis: How to Ensure Your Products are Accessible to All Users

- Product Definition /

- Product Design /

- Product Leadership /

Please note. While this article is relevant to every business, digital product or service across any industry I felt the healthcare examples were particularly relevant and important right now. Thank you.

We’re currently experiencing a global crisis that could previously only be imagined by a few. This event is also causing one of the largest scale behavioral shifts in history. Every facet of our previous ideologies is being tested. People are worried, tired, and frustrated. Things that only a few weeks ago were easy are now major challenges. How we connect, engage, and create value is transforming in real time. Out of necessity, the world is migrating toward increased virtualization.

There is also a key facet that was absent prior to these significant changes that now needs to become an integral part of every organizations’ playbook. How do you design for moments of crisis? How do you engage people? This isn’t something that can be managed in the aftermath. It is something that must be addressed now. Over the last several weeks I have spoken to close to a hundred different business and community leaders across the country. There is no debate on the urgency of these matters.

What Happens to People when Confronted with Crisis

There is a plethora of evidence that our psychological and cognitive abilities are altered when confronted with a crisis situation that induces extreme stress. In the midst of a crisis situation, our ability to ingest information, complete tasks, or make decisions is dramatically reduced. For most of us, we start with high levels of uncertainty and ambiguity. We struggle to grasp and understand what is happening and define it. The first major psychological aspect of experiencing crises is coping with uncertainty, ambiguity, and behavioral actions.

Let’s look at an example we can all intimately relate to. First, ask yourself when did you recognize the seriousness of COVID-19? How did it make you feel? When did it become personal? What did you do or not do? Hold on to those thoughts. All you have to do is read the stories that are released daily to get a sense of how many people have been impacted. The stress of a crisis can take many shapes and forms such as:

- Constant exposure through the media

- Uncomfortable personal, work, and public environments and the risk of exposure or high-risk conditions

- Intense pressure, scrutiny, and high expectations to resolve the crisis, or insulate those around you from its effects

- Being unprepared to operate in a new work from home (WFH) economy with social distancing

- Worry associated with knowledge of the dangers

- Worry or fear for your personal and family safety

- Witness to avoidable injury and loss, especially to children

- Intense emotional interactions with crisis impacted coworkers or family members

Designing User Experiences for Moments of Crisis

It’s easy to design a product or service for the ideal customer, someone who’s healthy, smart, and informed. It’s far more difficult, and therefore more important, to design for a more realistic user: still smart, but has been impacted by a potentially short-term or a life-changing crisis.

However, many of your personas, profiles, or practices focus on the ideal situation, but not someone in a moment of crisis. The best design thinking is inclusive of both. How many digital products or services are designed to help users who are confronted with extreme stress?

You can see this breakdown first hand by visiting one of hundreds of healthcare sites that have put up COVID-19 pages. The pages are filled with an overwhelming amount of information. While this might work for many people in the community looking to be informed, its value shifts dramatically if you or a family member are sick, looking to get help, and need to take action. For a healthcare organization, this impacts the ability to guide patients that are not in medical distress from inundating ERs and clinics. It imposes further demands on limited resources and capacity of caregivers doing as much as they can for as many as possible. Having a patient experience mobile app can open targeted channels of communication that avoid information overload for patients and their caretakers.

A crisis can take many forms, not having enough money to put food on the table, a relationship in conflict, losing your home, your car breaks down, you missed that important meeting, unexpected medical emergency, the personal safety of yourself or loved one is at risk. It’s not a comfortable topic. For many organizations thinking of someone in crisis at best would be an edge case, if considered at all. We can’t marginalize these use cases. We need to take them head-on, make them part of the discussion and be inclusive.

To address this we need to think about how our audience needs to be communicated to, guided, and engaged based upon the situation that they are in. To do this it starts with empathy and contextual awareness.

Understanding Empathy and Building New Insight

Empathy is about stepping into someone else’s shoes, letting go of our own biases, and seeking to understand a person from their own unique point of view contextually.

- Who are we empathizing with?

- What do they need to do?

- What do they see?

- What do they say?

- What do they do?

- What do they hear?

- What do they think and feel?

Developing empathy is at the heart of design thinking and designing for moments of crisis. It is essential for creating a deeper and more meaningful understanding of your audiences, so that you can develop the best solution to meet their needs.

When we design for moments of crisis we’re demonstrating respect and humanity for the people in that situation by considering the limited cognitive resources they have.

When we do this, we are able to cultivate contextual awareness that transforms our understanding and empowers us individually, and entire organizations to build better, and more impactful solutions.

In her TedTalk, Adrienne Boissy, Chief Experience Officer at the Cleveland Clinic, talks about the importance of empathy and how it is not a soft skill but an essential hard skill. When delivered properly, empathy has been proven to improve health outcomes. The human experience needs to be something that is much more humane.

In Moments of Crisis, Accessible Products Are More Important Than Ever

The success of any organization is based upon the accessibility of its products and services, meeting the wants and needs of customers (patients) when they have them. Yet, unknowingly, many businesses build invisible hurdles and bottlenecks that compromise their ability to effectively engage as many people as possible. Unfortunately, it is often not considered when thinking about moments of crisis despite being commonplace in the areas of operations excellence and agility.

One of the most common mistakes in customer experience and organizational design is thinking of accessibility as something to support people with long-term disabilities. The hard truth is that at some point in our lives we all deal with disabilities. If we are in pain from a burn and can’t use our hand to write or use the computer we’re dealing with short-term disability. Accessibility needs to be thought of as a practice in inclusivity. Ensuring that everyone can gain access to your products and services.

Some other examples of unexpected disabilities include:

- An injury that makes it physically hard or impossible to manipulate a mouse, keyboard, or other pointing devices

- Aging-related cognitive, mobility, or vision impairment

- Repetitive stress injuries like carpal tunnel, or tendonitis

- The onset of chronic disease, such as cancer or MS

Even being overtired or sick with the flu affects the ability to use online tools. At some point, nearly everyone will suffer at least a temporary obstacle to accessibility.

Accessibility is essential to your crisis design playbook, and should be a measurement of quality in the best and worst of times.

Five Design Principles That Keep Empathy in Mind During a Time of Crisis

1) Metaphor

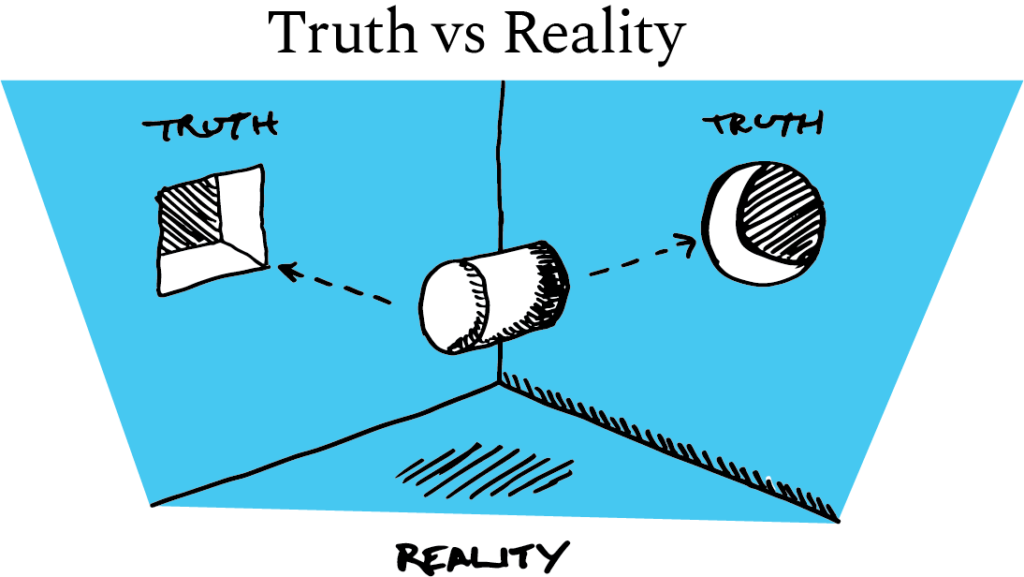

A new idea or complex concept can often be communicated more effectively by likening it to something the audience is already familiar with. This might be done with navigation, architecture, or content. Icons use metaphors to show rather than tell, and infographics can provide clarity while making something potentially dull (data!) more relatable and intriguing. Don’t mix your metaphors. Thoughtful and well-chosen metaphors make the abstract far more tangible, stir us emotionally, and take us further into the narrative.

2) Chunking

Information when grouped into familiar, manageable units is more easily understood and remembered. If information—especially when it gets complex—isn’t chunked into clear, scannable portions, you risk the user missing important information, or struggling too long to find what they need. In a crisis situation, this is vital. You need to prioritize and sequence if you want a clean and clear design that’s easy for a user to process, both mentally and visually.

3) Pattern Recognition

Organize similar types of information together. Our brains unconsciously will look for ways to simplify complex information, even when there is not a pattern. Consider how you can display information that encourages, by addressing an immediate need and internet outcome. Patterns can be on a single web page or mobile screen or across an entire digital experience. Look for ways to also clearly communicate where you are and where you have been to minimalize the need to reorient themselves or self verify that they have all the necessary information.

4) Contrast

Ensure you display information with visual contrast. It helps communicate the hierarchy of importance, differentiates information types, and consistently identifies points of action much more effectively. When scanning new visual information, we are unconsciously drawn to things that stand out against their surroundings. Contrast can be achieved through the use of positioning, size, color, typography, iconography, and imagery. Keep composition in mind. Inconsistency can negatively impact your users. Each choice should be carefully considered.

5) Limited Choice

People are more likely to make a choice when there are fewer options. For action, you want/need someone to take, limit the competing calls to action. Limit the number of choices and ensure the options are clear. If someone needs to make multiple choices guide them through a multi-step experience. Consider the sequence, each decision point people will encounter, how you can simplify this decision process and the path of discovery as you educate them along the way.

Each of these design principles is an opportunity to demonstrate empathy, make a difference, support inclusivity, and provide accessibility to all users, regardless of their situation. And, hopefully, your product contributes to the ultimate feeling of being, and feeling supported along a difficult journey. When users become so surrounded by an experience that, if only for a moment, they forget they’re even looking at a screen then you’ve succeeded in connecting with them.